Blood & Glitter: The Romantic Crossovers of “Interview With the Vampire” and “Velvet Goldmine.”

The intrinsic vampirism of rockstars, Rice and Haynes’ muse in Bowie, and my thesis on the musicianship of The Vampire Lestat.

*Contains spoilers for Interview With the Vampire (2022-) and Velvet Goldmine (1998)*

If we’ve spoken extensively at any point throughout the past month or so, you probably know I’ve been living and breathing Interview With the Vampire.

Season 2 of AMC’s 2022 TV adaptation of Anne Rice’s The Vampire Chronicles book franchise concluded on the last Sunday of June and, in the time it’s taken for me to let this whirlwind of a season finale sink in, I got to recap the season for EnVi and rewatch one of my favorite films: Velvet Goldmine (1998). It wasn’t a random decision — rather, I found my thoughts increasingly occupied by Goldmine again, after a certain announcement was made in the days leading up to Interview’s greatly anticipated June 30 episode. The show has officially been renewed for a third season, with AMC promising to usher to screen Rice’s Interview With the Vampire (1976) sequel, The Vampire Lestat (1985), which features Interview co-protagonist Lestat de Lioncourt (played in the series by Sam Reid) “starting a band and going on tour.”

Goldmine seemed to be everywhere post-press release, Interview fans’ sights set on getting it on moodboards for the series’ upcoming season by pointing out visual and narrative similarities between the two factually unrelated works, and theorizing about the route Lestat’s rockstar persona could (and should) go down. The consensus has been so loud that, as of the moment I’m writing this, Screen Rant has even published a piece about why Interview’s Season 3 apparently has numerous motives to imitate the film verbatim; And it has gotten even louder with the release of the introductory Season 3 trailer just two days ago, which pictures Lestat in full-on rockstar attire and attitude, warming up for an interview by snarking at crew members in the charismatic way only he can, and bringing to mind a vintage sense of rock stardom.

The 1998 movie — written and directed by Todd Haynes — tells the story of Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys Meyers), a ‘70s glam rock star withdrawn from the spotlight due to a death hoax in 1974, through the lens of journalist Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) who, 10 years after the incident, interviews several of Slade’s acquaintances to get insight into the musician’s life and where he may have wound up. Stuart himself, having come of age and into his sexuality as glam rock culture was flourishing in the UK, is seen reminiscing about his own past and involvement in the scene throughout the film, which culminates in his reconnection with Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), Slade’s colleague, antagonist, and ambiguous object of lust, whom Stuart once had a sexual encounter with.

Right off the bat, framing devices suggest parallels between the works; Biographical tales told through vignettes of recollections colored by narrators’ confessions and personal sentiments, and coaxed by characters who act as audience stand-ins. In Interview, Stuart’s equivalent is the 70-year-old investigative journalist Daniel Molloy (Eric Bogosian), who grabs what might be his last chance at another book in 2022, by accepting vampire Louis de Pointe du Lac’s (Jacob Anderson) invitation to re-do the interview they failed to complete upon their first meeting in 1973. Contrasting Stuart’s sensitive, self-insertive approach, the sharp-witted and cynical Molloy seems far removed from Louis’ gothic recountings as he wryly questions him at the 145-year-old’s modern Dubai penthouse at the start of Season 1. It’s during his stay that he comes to uncover his own part in Louis’ story, through unearthing memories from their 1973 session they had both been made to forget.

For what it’s worth, Louis and Molloy traded cocaine and blood in San Francisco around the time Slade was probably beginning to plot his fake death. Stuart was on his way to unveiling the truth about the lost star of his former idol for the New York Herald, roughly while Rice’s book Lestat awoke to the sound of rock and roll after a decades-long, vampiric slumber.

Lestat, by mostly AMC standards, is the volatile yet captivating Frenchman who turns Louis’ life upside down when, convinced he has found the companion he’s been looking for in him, he offers Louis the “Dark Gift” of vampirism. Throughout Interview’s Season 1, the vampire couple fall in love, “adopt” their surrogate daughter Claudia (played by Bailey Bass in Season 1 and Delainey Hayles in Season 2), and navigate a tumultuous domestic life in early 1900s New Orleans, before separating due to Louis and Claudia’s attempted murder of Lestat. Any ideas concerning bands and tours surface only at the end of the series’ Season 2 (spent with Lestat mostly absent, physically), which also marks the conclusion of the adaptation of Rice’s first TVC novel. In The Vampire Lestat, the book sequel where Lestat takes the music stage, ego casts a shadow over his desire to pursue stardom. Upon the meta publication of Interview, a book in which his selfhood has been twisted and warped by Louis’ perspective, Lestat is seeking to reclaim his narrative, doing what he knows best: Demanding the world’s attention.

This was pulled into an interesting direction in 2002’s Queen of the Damned, the second movie adaptation of Rice’s TVC, which succeeded 1994’s infamous Interview With the Vampire (starring Brad Pitt as Louis and Tom Cruise as Lestat). With nu metal at its peak around the year 2000, Queen explores a pocket where Lestat (Stuart Townsend) howls in Korn’s Jonathan Davis’ raspy timbre over abrasive guitar riffs and rhythmic stomps. There is just a tinge of that gothic darkness, vampiric lyrical themes about hunting and feeding on humans as co-written by Davis to tie into Rice’s writings, Townsend’s golden-ratio face and contrived badboy demeanor at odds with the downtrodden, lonely in immortality vibes constituting his performance’s premise, heaps of black pleather, camp for the ages. Something about Lestat’s hypostasis as a character doesn’t quite translate1 — and, perhaps, it’s somewhere around these parts where it becomes evident how the 2022 show’s unique tapestry of narrative liberties and lack thereof has been able to land it the street title of “Best Show Currently on TV,” as opposed to “Loading Cult Classic.”

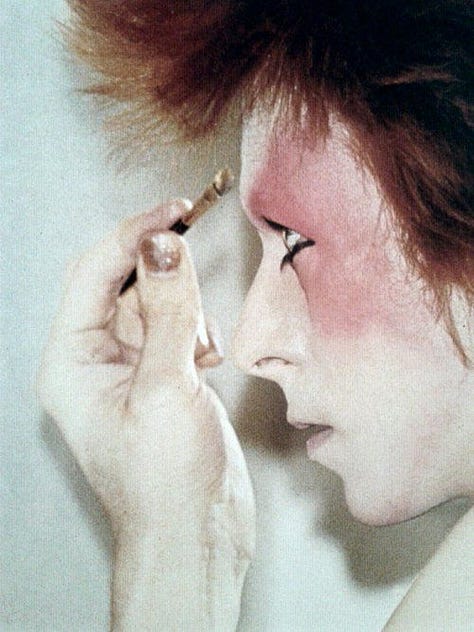

Though the TV adaptation will allegedly be shifting his rockstar arc’s timeline to the 2020s, instead of the novel’s 1980s, it is almost impossible to divorce Lestat, even as portrayed in the show — especially as portrayed in the show — from his New Romantic, golden rockstar era sensibility. And while glam rock’s novelty had already dimmed by the late ‘70s, when provided with the context of the arc, it feels instinctive to hold the image of a flamboyant, androgynous Lestat elaborately dressed as King of Mardi Gras in Season 1’s finale2, next to Bowie’s extravagant yet dandyish costumes — in the lineage of Lestat’s mid-to-late 1700s origin3 — and abundant face paint from the early part of the decade. Bowie, who saw an overwhelmingly embellished biopic in Goldmine, as his persona also largely informed Slade’s, down to the invocation of a hyperreal, performative alter ego. (“Maxwell Demon” might as well be a euphemism for “Ziggy Stardust” in the film.)

If anything, Anne Rice’s conception of rockstar Lestat may have followed a similar train of thought. In a Vogue piece published in November 1983 — two years before TVL saw the dark of night — and titled “David Bowie and the End of Gender,” Rice writes about the musician who has been dubbed “proto-Lestat” by TVC fans:

One moment he is delicate, vulnerable… the next, harsh, powerful. Always, Bowie is a startling performer — he’s giving androgyny a good name.

Among Lestat’s characterizations, the aforementioned word “volatile” reigns supreme. His tempestuous personality — mostly as recounted in the series’ interview by Louis and his partner of 77 years, Armand (Assad Zaman), who also shares complex history with him — oscillates between tender expressions of affection and explosions of toxic, masculine aggression that quickly add up to an abusive pattern. Lestat’s manner of carrying himself, as brilliantly depicted by Reid, is enveloped by a borderline feminine allure — like floating or dancing on tiptoes through the world, with his long, blonde hair always waving in the wind — which gets juxtaposed against the added volume to his figure achieved through sturdy, padded suits that enhance the broadness of his shoulders while often accentuating the waist.4 For the duration of Interview’s first two seasons, Reid’s Lestat is a performer, too; The true essence of him remains unreached, masked and obscured by narrators’ projections until the end of Season 2’s finale, which sees him and Louis reunite in the present day, their dynamic unobstructed by third parties for the very first time in the show.

While Louis and Armand’s retellings help paint a relatively cohesive portrait of Lestat, it is that gut-wrenching scene that ultimately reveals a side to the character which, beyond highly emotional and campy, is extraordinarily vulnerable in its rawness, hints of introspection, and the funny implications of his general… strangeness. (Get a load of this over-250-year-old guy in his wreck of a home, asking Siri to pause his classical music while holding his emotional support plank of driftwood colored over to resemble a piano.) It is that very strangeness, drawn from the show’s single realistic glimpse into Lestat, that convinces viewers to take him somewhat seriously when, in the same scene, he seemingly half-jokingly announces his plans to go on tour after he’s had “50 more years of practice”; and that strangeness which naturally provides the framework for next season’s mood and texture. Lestat, Rice’s most honed and vivid creation whose extensive lore spans several of her TVC novels and whose only human attachment is explicitly none other than music, contains multitudes. It only stands to reason that a rockstar could be made in his image.

“No auto-tuning. No trigger warnings. All feels amplified,” writes AMC’s Season 3 press release, and that certainly corresponds to Lestat’s already well-known flair for the dramatic. The expressly impactful, riveting swings and pacing of Interview’s Season 1, as experienced by Louis at the junction of social upheaval in New Orleans and his personal journey from human to vampire, give way to more subdued, intricate maneuvers in Season 2, as the controlled chaos of Paris comes into the picture through Armand’s stepping in to share the narrative. Lestat’s point of view is bound to differ, perhaps even taking the show in a completely new direction tonally and stylistically.5

Still, despite being secretly obsessed with the fan-favorite idea of a deceptive music documentary format (à la Daniel Molloy’s journalism course ad in the pilot’s intro) where Molloy takes to interviewing Lestat for his own book sequel — which, based on the freshly released Season 3 trailer, AMC seems to be leaning into; I’m not really here to construct the argument that Interview’s Season 3 should emulate Goldmine and its particular docu-structure, maximalist aesthetic, or rock opera sensibility. Rather, I’m more fascinated by some of the intertwined contexts, themes, and implications that subliminally connect Lestat’s world with Slade and Wild’s.

Time, places, people,... they’re all speeding up. So, to cope with this evolutionary paranoia, strange people are chosen who, through their art, can move progress more quickly.

Goldmine’s Mandy, Slade’s ex-wife played by the stellar Toni Collette, gives reporter Stuart her interpretation of what rockstars represent in culture almost halfway through the 1998 film. She also labels “dreaming” a default “essential” to the “character of the rockstar.” Rice, in her 1983 piece, had already weighed in passionately:

Whirling on the very edge of culture, the great rock singers of our time personify our laments, our fears, and our dreams. They are the fantasy figures of the romantic artistic vision, set free to evolve on record and in live performance exactly as they please.

Strange, hyperreal, dramatically-inclined, and perfect vessels of androgynous sensuality; rockstars are inherently vampiric.

The notion of Romanticism, in the late-18th and early-19th century artistic sensibility sense, is embedded in the fabric of every vampiric story — prioritized and honored in those who substantially respect themselves. This is what Interview nails, as also argued by Judy Berman in an essay for Time Magazine, where she contextualizes: “The [Romantics] rejected the cold reason and empiricism of the Enlightenment in favor of the irrational, the supernatural, the emotional, and the deeply subjective.” Interview’s universe — while practically attached to reality, with curt, grounding moments often serving up comedic effect — soars with the heightened emotionality that is intrinsic to vampiric nature and its constant acknowledgement of immortality. Subjectivity, too, lies at the heart of it all, woven in as the underlying danger of recollection and regarded as the central premise on which situations are swayed. In other words, this is a prime example of a character-driven story.

In the aftermath of World War II, rock and roll was born — and Romanticism, in all its deathly, tragedy-worshiping, egocentric glory, was back on stage for the second half of the 20th century. I always return to a few words by Björk6 which I find encapsulate the spirit of this era particularly succinctly — and that Of The Moment readers might remember from a past essay. Let me quote the iconic Icelandic musician again, on how the cultural shift from the “post-post-post” ghosts of the past to a biotech-oriented future felt right before the turn of the millennium, when she released her debut solo album. Or rather, quote myself paraphrasing her (please forgive the over-indulgence):

In hindsight, Björk describes this premature vision of the future as biology and technology working together; a departure from dark, gothic, industrial, Romanticism-inherited, Baudelaire and Bukowski-adjacent sensibilities, and movement towards “quantum physics, the vibration of the atoms, going on a spaceship for the first time out of our solar system”; [...] the ego death; a dethroning of the human and everything adhering to individualism or the centering of the self, similar to a Shakespearean play or a Greek tragedy, and of course down to the handiwork of the guitar solo — which Björk jokingly [characterizes] as “illegal” in regards to the times.

Disregarding the rockstar’s kick out of a zoomed-in shot of fingers expertly working chords and the resonance of sound produced directly by skin across giant crowds, representing a kingdom for a king and an audience for the mythology of the idol, nightclub habitués of the era aimed for a state of deep, oblivion-inducing trance, the sound-makers behind them reveling in the subversion of the human scale to music by adopting the ceaseless monotones of synthesizers, looped into hypnotic motifs until the first cracks of sunlight.

“Blood, graveyards, suicides, bats, vampires,” are some of the words that come up as allegories in Björk’s descriptions of the cultural and musical climate up until the ‘90s. The culmination of this sentiment, of course, took place in the ‘80s — the period when Rice started laying down the ground rules for the vampire genre — whose signature over-the-top, dramatic aesthetics are a source of nostalgia to this day.

Theatricality and physicality might be the two axes that define the person, self, or human, as a focal point of art — and, for the latter, nothing speaks as loudly as the innate associations of vampires with specific body parts such as the neck, mouth, and hands. (If anything, any vampire interested in picking up the guitar at least has the manicure aspect resolved for life under the laws of Rice’s universe.) Similarly, it’s no secret how reliant the rockstar’s performance is on physicality. Goldmine, especially, makes sure to emphasize its impact through the character of Wild — the yang to Slade’s yin — whose explosive, unrestrained, and not far from vulgar stage presence (drawing from the mythology of none other than Iggy Pop) wholly entrances Slade at first glance. As Wild’s persona starts rubbing off on Slade on their shared touring excursions later in the film, it is their highly physical, sexually charged antics on stage that end up having profound ramifications on young Stuart’s life, when he’s caught masturbating to a photograph of the two and kicked out of his parents’ house.

We don’t have to look further than the scene in which Slade lays eyes upon Wild for the very first time as the latter is performing on a festival stage, to assess the effect of theatricality, too. Rhys Meyers’ languid, dazed yet tension-filled gaze in that moment of Goldmine, as well as his character’s raw admission of jealousy within the following minute, resembles Zaman’s bewildered expression of simultaneous contempt and longing upon Armand and Lestat’s first encounter — revealed through flashbacks in the third episode of Interview’s Season 2. It’s 1794, the threshold of the Romantic era, when Armand goes to see Lestat, then an actor, perform at the theater in the role of the Harlequin. A timid leader of the god-fearing, medieval law-abiding, and sheltered Paris coven for over 200 years, Armand identifies in the boastful, makeup-adorned face of Lestat freedoms he had been repressing and denying himself and his coven in favor of discipline and humility.7

Eighteenth century Lestat “prancing and preening,” and bewitching the crowd from the wooden stage with his “entirely unnatural” charm, as Armand puts it, could be just a little taste of his innate proximity to rock stardom. It goes hand in hand with his acceptance of his vampiric nature, cultivated years after a harrowing turning, which triggers a need for a liberating, fulfilling existence, away from rules and restrictions. Lestat’s vision for the Théâtres des Vampires, a theater whose facade is to be used as cover for vampires luring in human victims to kill during plays, which he bestows on Armand, presents the coven with an escape from the shadows; a method of blending in with humanity, while simultaneously being given the chance to unleash their predatory instincts fearlessly.

In rockstars, we have historically confronted unapologetic expressions of our id-level inner selves that seem to defy the status quo, in order to exist in their truest, most animated and attention-demanding form. We have loved them, hated them, loved to hate them, wanted them, wanted to be them, envied them, lusted after them. The theater, in Interview, and the concert stage as well as the press conference, in Queen, are settings where the audience’s wilful ignorance is exploited by vampire-actors and vampire-rockstars alike; devices that allow them to publicly “reveal” their nature in the context of pretense — a play, a persona — thus living as their real selves while hidden in plain sight. In vampire fiction, vampirism assumes the role of a supernatural veil which envelops amplified stakes for all ideas surrounding humanity, from behavioral to existential. The Romantic theme of exaggerated selfhood lies at the heart of the vampire genre and, of course, in the meaning of the aforementioned point about the centering of the “human.” In the words of Interview producer Adam O’ Byrne, “vampires are the most human monsters.”

A popular concern regarding the path Interview’s Season 3 seems willing to go down revolves around archetypical rockstars’ relative irrelevance in mainstream culture. It makes sense that the lack of collective sentiment that would prop up a rockstar, as defined by later 20th century standards, would be a result of what Berman refers to, in her Time piece, as “internet-mediated realism,” the exposure-induced, disaffected tone plaguing even the most romance-oriented film and TV of 2024. Indeed, it is difficult to suspend cynical ideas about unfiltered emotion and romance so powerful it transcends lifetimes in the age of the “aura” and the “situationship.” To accept the irrational as reality, over the rational — or, in the case of rock stardom, let into your heart the indulgent urge to worship a god-like creature amid a climate of disillusionment with higher powers of all sorts.

What AMC’s Interview achieves, in terms of fully leaning into the Romantic sensibility of its source material, is no small feat, and the show wears its capacity to elicit strong reactionary feelings as a badge of honor which allows it to stand out amid the current TV landscape. Nonetheless, the promise of an expanded contemporary timeline raises a challenge of tonal balance. And with the pull of golden day-fashioned rockstars not as valid in 2020s pop culture, one might wonder if the series’ remaining Romantic chops and the sheer whimsy of its choice will prove enough to hold this new arc together.8

If we’d like to be consistent with Goldmine’s Mandy’s quote cited above, which credits rockstars with spearheading cultural progress, for such a figure to occur today, they would have to exist “on the edge,” as Rice says — to be a projection of ideas unprecedented and unforeseen, ideas of genuine novelty. Yet, ‘70s-sculpted Lestat’s intrinsic attachment to nostalgic molds is so prominent that when it comes to placing his character and presentation in a modern musical climate, the angles to the contemporary rock scene I find most approachable pertain to two frontman personas who carry themselves with undeniably old school stage flair. I think of Måneskin’s Damiano David, as far as shameless narcissism and superficiality goes, whose naughty theatrics and androgynous styling recall rock stardom from eras past, with a maximalist, sleek yet dirty, and tongue-in-cheek attitude to match — not to mention pop appeal, in spite of intelligible critical gripes with the group’s recent music. On the other end of the spectrum, there is the charismatic and sensual performance of Arctic Monkeys’ Alex Turner, as it has evolved across the band’s latest projects, where mellowed out, ‘70s-influenced instrumentation and elaborate, romantic lyricism call for suave grace and elegance on stage.

The latter example here would hold greater sonic proximity to Lestat’s musicianship as depicted in AMC’s show up until Season 2’s finale, with its emphasis on classical structures and the vampire’s infatuation with the piano. Interview’s singular sample of Lestat as a recording artist from Season 1, the ballad “Come to Me,” written realistically by composer Daniel Hart9 and fictionally by Lestat “in the music of the hour” back in 1937, is a Valentine featuring delicate, orchestral instrumentation wherein the Frenchman croons lovelorn lyrics with technical precision. By modern standards, this is not unlike a sound 2020s audiences may have reacquainted themselves with through someone like Laufey, the 20-something Icelandic songstress utilizing musical vernacular that dates back to the 1930s to craft pop love songs with a mid-century musical theater sensibility10. YouTube creator Adam Neely puts it as “mid-century pop” in this essay, where he also notes some similarity between Laufey’s “Let You Break My Heart Again” (recorded with the Philharmonia Orchestra) and the 1937 Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs classic “Someday My Prince Will Come.”

Thesis territory: There are several ways in which this sensibility can be directly translated into the sphere of rock music at large — but, on a personal level, a couple stand out. Coincidentally or not, both from the critical, in Interview’s universe, year of 1973 — and both massive inspirations for Haynes’ Goldmine. In his ‘73 record Aladdin Sane and specifically the song “Time,” Bowie paints a metaphor for an afterlife, or an adjacent realm, using the uncannily Lestat-esque device of the theater. But it’s the poetic balladry of the album closer, “Lady Grinning Soul,” which carries it a step further while fully embodying the croony, classically-inclined, and jazz-influenced musical identity of the vampire — and whose virtuosic piano flourishes and trembling falsettos are additionally echoed in some of the aforementioned Arctic Monkeys’ later work. Ben Gerson writes for Rolling Stone in 1999:

All the world’s not a stage, but a dressing room, in which “Time” holds sway, exacts payment. Once we’re on, as in all theaters, time is suspended and will no longer “In quaaludes and red wine” be “Demanding Billy Dolls” — a reference to the death of New York Dolls drummer Billy Murcia in London last summer.

The appeal to an afterlife, or its equivalent, which is implied in this song, using the theater as its metaphor, is further clarified in “Lady Grinning Soul.” The song is beautifully arranged; Ronson’s guitar, both six-string and twelve, elsewhere so muscular, is here, except for some faulty intonation on the acoustic solo, very poetic. Bowie, a ballad singer at heart, which lends his rock singing its special edge, gives “Lady Grinning Soul” the album’s most expansive and sincere vocal.

Neighboring Bowie within the glam rock canon and on the roster of real-life figures that informed Goldmine’s Brian Slade as well as the film’s soundtrack is, of course, Roxy Music. I’d like to point towards one of the ensemble’s discography landmarks and the star of their ‘73 album, For Your Pleasure; “In Every Dream Home A Heartache,” a “two-part essay about interiors and illusions” as defined by Rob Tannenbaum for Pitchfork, pulsates with all the melodrama of a theatrical monologue and revels in macabre humor as Roxy frontman Bryan Ferry half-offers ironic musings on consumer opulence and the immaculate modern home phenomenon, half-serenades a blow-up sex doll. Over hypnotic funeral organ and hints of saxophone embellishments that calculatedly underscore his off-form intonations, Ferry sounds like the only man left on earth — his all but atonal performance transfixing, up until the three-minute mark’s distorted guitar solo explosion accompanied by anguished chants. “There are glimpses of modern sophistication, but behind it, only horror,” Tannenbaum writes, comparing Ferry’s dramatic baritone to Dracula, and adding:

Ferry, with his fondness for dualities, uses theatricality and even camp to prove his sincerity, implying that everything make-believe is also real, and vice versa.11

A tidbit worth noting is that Ferry revisits the stunning For Your Pleasure cut with a new angle in his 2002 record Frantic and the track “San Simeon,” a “return to ‘Dream Home,’ or an extension of it,” in the musician’s words. A mesmerizingly haunting piece drenched in gothic ambience and layers of orchestral instrumentation that soar in lush crescendos, “San Simeon” gives the impression of having been recorded in the eponymous “fairytale castle” belonging to American newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, centuries after its abandonment, as the tormented cries of ghosts still linger, echoing through the walls. Ferry says in his 2002 Uncut interview with Chris Roberts:

I found this set of lyrics I had from when I was writing “Dream Home” in ‘73. Some of these, which I’d left out and never used, were perfect for this song. [...] You wander into the song and you’re in this kind of ghostly castle, where all the memories of a very glamorous past come flooding in on you. This house was the party place for [...] all the greats of Hollywood’s early days. The whole idea of this appealed to me. It was rather wistful and... Proustian.

Perhaps further from the rock canon than the selections above, but surely the closest to our vampire’s displayed musical inclinations and gothic origin. You could argue that nothing screams Lestat as much as Ferry’s vivid yet reverent delivery of snapshots of pure decadence involving “baronial great halls,” “teasing in French lace” and referring to a past flame as “fantasy playmate, candlelight lover” — juxtaposed against the knowledge of impending doom. Flashbacks of Interview’s Season 1 shine through “Lie on your lush lawns, waterfall bubbles / Drink at my fountain, forget all your troubles,” just like in the Season 2 finale’s reunion scene which depicts Lestat stuck in limbo between the memory of glory days in 1930s New Orleans and the image of that metaphorical “fairytale castle” physically crumbling down in the face of a hurricane.12

Some of the above is certainly present in the first taste of rockstar Lestat as we will come to know him through Interview’s upcoming season. “Long Face,” assumingly Lestat’s debut single, sounds straight out of the ‘70s glam rock scene — yet boasts accessible, pop structure and upbeat rhythm fit to get a concert crowd going, despite its affected, occasionally French lyrical touches. Bowie practically screams through the track, though not in his soulful “Lady Grinning Soul” cadence, but something much more akin to Aladdin Sane’s penultimate cut and record standout “The Jean Genie.” It’s the hilarious brand of Lestat’s narcissism in a bottle, a bonafide blast from the past, and as a result, appropriately cringe through a contemporary lens. An approach that betrays the character’s grand expectations, capturing his presumed skim of recent pop culture and desire to immerse himself in it, rather than tapping into the deeper parts of his origins; and one that puts production’s plans of crafting “a little pop masterpiece” inspired by the likes of Hedwig and the Angry Inch and Rocky Horror into action. Evocative of aspects of Goldmine’s soundtrack for sure, though falling slightly short in terms of gravitas — maybe intentionally so.

Ferry or Roxy, for that matter (or the aforementioned Måneskin and Arctic Monkeys), surprisingly don’t seem to be mentioned in the long list of inspirations for Lestat’s rockstar persona revealed by showrunner Rolin Jones at the San Diego Comic-Con two days ago, which expectedly includes the Goldmine-crucial names of David Bowie and Iggy Pop — as well as contemporaries like Nick Cave, and lineage artists such as Florence Welch, St. Vincent, and even Fiona Apple. Their presence in Goldmine is palpable, however, whether through Haynes’ soundtrack picks, stylistic accents specifically pertaining to Roxy synth weirdo Brian Eno’s attention-drawing, feathery stage wardrobe, or worldplay-driven allusions.

My initial observations13 around the enigmatic figment of Jack Fairy who, in Goldmine, is credited (namely by Mandy) with having launched the concept of glam rock onto the music world, were what triggered the first mental drafts of this piece you are currently reading. An iconic yet nonchalant prototype “everyone stole from” who, in a way that would resemble a guardian angel or friendly ghost, elegantly drifts in the movie’s background without ever engaging in the boisterous, chaotic shenanigans his descendants are seen throwing themselves at, Jack Fairy is theorized to embody a metaphysical entity of Ferry and Eno merged together. Add to that the visual hints recalling Marlene Dietrich’s signature beauty look that render the character’s androgyny a focal point. And, of course, his association with Oscar Wilde, implied in the film to be a progenitor of, well, everything. The Wildean thread anchored to Jack Fairy — tangibly represented by a green jewel passed down to Curt Wild at the end of the film — as well as his unchanging, youthful look and uncanny aura play into the figure’s perception as a borderline fantastical manifestation of queerness and freedom. Haynes states in Australian newspaper The Age in 1998:

My research process was retracing the steps of what I understood Bowie and Bryan Ferry and a lot of the key architects of the glam sound and ethic went through. [...] The way they arrived at what they were doing was through a great many cultural references, from literary to cinematic to pop, particularly the Warhol scene. And in a way, all roads kept leading back to Oscar Wilde.

I saw a parallel between the ways Oscar Wilde was attacking the romantic tradition that preceded him, inverting these precious notions of the artist in nature and the direct, authentic expression of the soul. He asserted the external, the artificial, the surface elements of personality and pose and made that the place you looked for meaning as opposed to this notion of depth. I saw that echoed in the glam era. [...] [Jack Fairy] is meant to stand for the instinctive origin to the glam idea, of which Brian Slade was the more self-conscious appropriator.

The particular, miraculous contradiction of glam rock, then; If rock is romance, glam is its veil — and adorned with it, rock perhaps appears even more romantic than before. All it takes is a made-up legend for humans to become superhumans who help us think about ourselves. All it takes is a made-up legend for humans to become monsters who help us think about humanity. Tied together by heightened emotionality that amplifies romantic ideas only through concealing them, glam rock stardom and vampirism render the stage their comfortable home, where the context of pretense allows for expressions so instinctive they seem far removed from truth.

Jack Fairy — Brian Slade, David Bowie, Lestat de Lioncourt, in the eyes of many — is the “real” thing which, of course, isn’t real. I wonder if that is essential to a tale — one that, in Interview, is explicitly meant to seduce. If the art of good storytelling itself hinges on subjectivity convinced it is anything but. Haynes wanted his film, which explores past events through multiple perspectives, to feel like “a dream, in a way — a dream of glam rock, something more sumptuous and rich and multi-textured than it was for people who might have lived through it.” And if that doesn’t encapsulate Interview’s “odyssey of recollection” — some glitter always finding its way into the blood.

Thank you infinitely for reading, and even more if you made it to the end.

Comments are always welcome and appreciated.

Worth noting that Rice's stance on the film remained quite ambivalent for several years, mostly due to the studio's lack of consultation with her over the script development and their disregard of the source material.

Costume designer Carol Cutshall on Lestat's King Raj costume via Instagram:

I was inspired by men’s corsets, Victorian fan lacing, straight jackets and institutional restraints. [...] It needed to have both masculine and feminine energy. Lestat was everything to everyone.

Costume designer Carol Cutshall on Lestat's fashion via AMC:

For Lestat, he's coming from the mid-to-late 1700s and that was during a real explosion of dandy fashion for men. It's like Beau Brummel, the most widely known male dandy fashion plate. As we move forward with Lestat, I looked at icons like Rudolph Valentino. We have to remember that Lestat is coming from a time when clothing was a lot more restrictive. He wears modern clothes, but they almost fit him like corsetry, even his suits.

More of Rice on Bowie and his unyielding softness as British Major Jack Celliers in Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (1983), even in the face of battle:

[…] Bowie as the courageous British soldier never loses his androgynous allure. Even battered and soiled, he is a golden blaze of lissome gesture, seraphic facial expression, satin hair. No matter what the action demands of him, there is an entrancing rhythm to his movements.

Who, very unexpectedly, has a spot on the roster of rockstar Lestat inspirations, according to showrunner Rolin Jones.

Let's note here that, if anything, vague parallelisms between Lestat and Wild are a main takeaway from the show's Season 3 trailer, looks included.

That is, of course, unless we find ourselves at the threshold of a massive cultural shift by the time the season airs, or they genuinely make Lestat a flop (which would be both highly possible and insanely hilarious). The arc, regardless, remains another instance of production's "Anne, first" approach. It could be argued, in that sense, that the series' fierce loyalty to the novel franchise's happenings, despite their character-related liberties, places the show in its own timeless bubble.

Who toured with Bowie for a time, by the way.

Reid's musical theater experience certainly results in an up to par vocal performance in that department.

How much of a coincidence would it be that those two songs (“Lady Grinning Soul” and “In Every Dream Home A Heartache”) are the ones at the top of Luke Brandon Field’s (who portrays young Daniel Molloy in the series) playlist for Molloy, consisting of predominantly ‘73 cuts?

Bryan Ferry cites the opening scene of Hitchcock's Rebecca (1940) as subliminal inspiration for “San Simeon,” yet my mind also goes to the opening scene of The Phantom of the Opera (2004) and the auction taking place at the abandoned Parisian Opera. Fun fact, as per the book’s original timeline, Interview’s Paris-located events are supposed to be taking place around the same time as Phantom’s. Looks like you simply had to be there.

In Daniel Molloy journalistic note format:

JACK FAIRY

Green pin that allegedly belonged to Oscar Wilde

“Everyone stole from Jack”

Unaging

Blood repurposed as lipstick in flashback

Vampire???